Folks, in case I haven’t found you through another algorithm yet, I want you to know that—after a year and a half—I have a new song out, “Monsoon Season”, to kick off the next era. This one is a window into what’s ahead, so I wanted to be vulnerable and let some of my more intentional listeners into more of the story behind this record. Heads up, this is a heavier post than usual and will include reflections on addiction and suicide. If you read on, I hope you’ll see why I felt Easter weekend was the right time to put it out there. My dad and I believe telling these stories can chip away at some of the stigma that makes it even harder for those of us struggling to find help.

Alright, let’s dive in. This is the story of “Monsoon Season”.

For those who aren’t familiar, monsoon season is a uniquely important time of year for Arizonans, especially folks in the Valley. Starting in July, the 118-degree (but dry!) heat of Phoenix is interrupted by occasional, out-of-nowhere thunderstorms and flash floods. For most of us, it’s fun—the temperature can drop into the 80’s and the rain, being so rare in the desert, is a cause for celebration. As a kid, I was mesmerized by the roar of the howling winds as they rattled our house like a tin can, reverberating in the swamp cooler that had been rendered useless by the wave of humidity.

But growing up in the pool business, monsoons are less fun. My dad opened “Jerry’s Friendly Pool Service” on my first birthday. I don’t remember when I cleaned my first pool, but I remember tagging along on his route, passenger-side in a white pickup littered with tangerine skins and broken chlorine tablets. My dad had bought a bunch of accounts from my aunt and uncle as he moved from brick-laying to a more comfortable, steady line of work. Come monsoon season, though, “comfortable” and “steady” were a stretch; the heat had us up at 4am and the tornado-like aftermath of the storms doubled our cleaning time and tripled the cost of chemicals, even as Friendly’s month-to-month bottom line continued to rely on December pricepoints. It was an annual kick in the pants.

For my 16th birthday, my dad gave me his work truck along with a route of my own, which I’d sandwich between school, church, and football. I was glad to have a flexible gig and the car with the best A/C. So when I left for college, by which time I’d probably cleaned thousands of pools, chlorine was in my blood, and maybe not just metaphorically—I was worried I’d get some kind of rare cancer from all the bleach byproducts I’d absorbed. The jury is thankfully still out on that one, though my cousin allegedly lost his sense of smell after a bad brush with a bucket of shock. If I try, I can still smell it, even feel its chalky-then-slippery film on my fingers.

I was the first generation in the family with Google maps, so I sadly don’t know the Phoenix grid system the way that my dad does, having navigated it all-analog as a poolman for close to 30 years. The mid-century city would’ve made Robert Moses proud, what with its sprawling grid and single-floor suburban farmhouses. (Robert Moses is one of the most famous city planners of Manhattan, an early grid city that ironically and poetically rejected his idea of freeways looping around skyscrapers and carving out communities—an idea that was quickly exported to fertile deserts like Phoenix, where canals and A/C were making mass civilization possible for the first time since the Hohokam had figured it out some thousand years ago.) Today, over 5 million people live in the greater Phoenix area, up from around 50 thousand in 1930. You can drive for an hour at 70mph without hitting a stop light and still be in metro Phoenix. So by the time I was 18, for all its luxurious space, Phoenix was beginning to feel paradoxically claustrophobic.

Of course, my readiness to launch wasn’t just a product of urban planning. Another crucial thread in my self-story is addiction, which is really where this song, record, and era are all heading. I had my dad read this post before I put it out, and like I said, we agree that some stories are worth telling.

My parents met in Alcoholics Anonymous in the 90’s. My mom had been a flower-child breed of hippie—mostly acid and peyote with alcohol as her latest sparring partner. My dad, on the other hand, was some sort of outlaw-hippie hybrid, having dealt heroin to gangs like the Dirty Dozen and the Hells Angels before going to prison for forging opioid prescriptions. He’d lost his brother to drug-related suicide, his dad to alcoholism, and dozens of other loved ones to drugs. Alcohol was the tip of the iceberg, but thanks to methadone, a form of medication-assisted therapy, he’d managed to get sober from other narcotics just as the opioid crisis was really kicking off, precipitated by Purdue Pharma’s aggressive marketing of OxyContin and the infiltration of the American drug market with lethal fentanyl. But that’s a story for next month.

I grew up being reminded that my dad was a walking miracle, his testimony serving as hard evidence of Christ’s’ radical healing power. Partly due to the stigma surrounding medication-assisted therapy, he was off methadone by the time I was born and was sober until I was in middle school. My concerns weren’t about him using or overdosing but about him dying from some complication of hepatitis C, a liver infection classically transmitted through unsterile needles, to which my dad had been no stranger; you can still see the track marks on his arms. So when my dad’s participation in a clinical trial cured the hepatitis, we praised the Lord for the advent of such a wonder drug. That was the first time I considered medicine as a profession.

But the monsoons make pool work harder, especially with a bad back and an unreliable truck. My dad had a minor back injury that he re-injured again and again thanks to the lack of power steering, which seemed like a reasonable trade at the time, given the A/C was out in the old workhorse. The timeline is blurry, but somewhere along the way a doctor prescribed Purdue’s now infamous OxyContin, an extended-release form of oxycodone that he was told had a low risk of addiction—another wonder drug? And so his sparring partner triumphantly returned, along with painful cycles of blame, shame, and secrecy.

Over the next few years, our relationship was strained by the weight of the habit. We’d always been close, and in what my dad now recognizes as a severe misjudgment, I became his sole confidant at age 14, hiding Oxys at his request so that he didn’t take too many. It mostly went on without a hitch, though I distinctly remember a time in which he’d misplaced a bottle and thought I was hiding it to sober him up against his will; the conversation ended with me slamming the door in his face and both of us collapsing into tears. My mom and sister didn’t find out about his Oxy habit or our arrangement until I was 17, and you can imagine how that felt for everyone. I thought I’d been helping, so I felt waves of confusion and guilt as I watched my mom pack the car to stay somewhere else for the night.

Through a Herculean feat of willpower, my dad managed to taper himself off opioids without the assistance of a treatment team. I’m only now coming to realize how difficult that must have been, welcoming back those brutal withdrawals that had pushed him to the edge of suicide back when he was in prison. He managed to stay sober while I was away at college and then off pursuing songwriting in Nashville. It was on Good Friday 2023, almost exactly two years ago, that I received a call from out of the blue letting me know that my dad had overdosed on fentanyl.

The third wonder drug in this story is Narcan (naloxone), which can instantly reverse an opioid overdose. As a fourth-year medical student, it’s ironically the only medication I’m allowed to distribute under state standing orders, though that’ll change when I graduate next month. My dad received repeated doses and, in Christ-like fashion, was home from the hospital on Easter morning, 3 days later.

Two years isn’t long, and each of my family members and I will probably spend seasons of our lives processing and re-processing our family’s addictions. My dad’s recovery has gone remarkably well, thanks to his supports, both medical and otherwise. For my part, I’ve found books like Beth Macy’s Dopesick and Sam Quinones’ Dreamland to be especially illuminating in understanding how a story like my dad’s has become so tragically common in America. I’ve also found faith, family, friendship, and therapy to be crucial supports. This song, “Monsoon Season”, and the album to follow are the creative byproducts of these last couple years of going inward and outward to gain a new perspective.

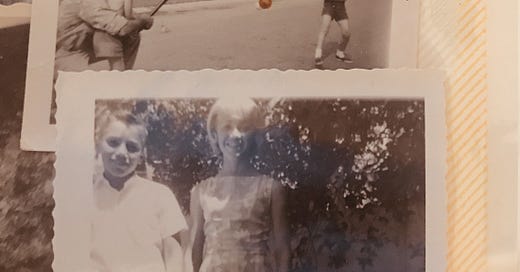

Over the next year or so, I’ll be using this space (Substack and Patreon) to tell stories, both my own and those of others, stemming from the American opioid epidemic, starting with its origins. “Monsoon Season” is one of the last songs on the album but felt like the first I should share with you. I wrote it as an encouragement, a sort of Eastertide benediction to my younger self, who oscillated between gratitude and despair in a sprawling grid of swimming pools and freeways. It’s the Easter morning of the album, the moment of resurrection. You can watch our DIY music video, featuring my dad and family, here.

For those of you who are paid subscribers, you can hear next month’s song below. I’m grateful to start this next chapter with you.

Happy Easter to you and yours.

-J

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to J Lind's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.