The first thing I ever said I wanted to be when I grew up—before I wanted to be a marine biologist, a herpetologist, an archeologist, a doctor, or a philosopher (in that order)—was an artist. But I wasn’t thinking about music or songwriting. I wanted to draw.

At 5 or 6, I’d try to sketch Saturday’s cartoons as they swam by, reimagining them wearing different clothes or interacting in new places. My dad proudly showed off my drawings to church friends and clients of his swimming pool maintenance business. “And without even tracing”, he’d say, revealing his hand from behind the thick white paper, demonstrating beyond a shadow of a doubt that this wasn’t your classic see-through tracing scam. No, this was real. This was art.

My love of drawing took on a new dimension in grade school as it grafted with another budding passion: fantasy. Despite growing up evangelical, it wasn’t the Christian apologetics or theological writings of C.S. Lewis that initially grabbed me but his fantasy world, Narnia. My 2nd grade teacher Mrs. Freeland read us The Magician’s Nephew, and I was hooked. I breezed through the 7-book series around the same time that I stumbled upon J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, which to my eight-year-old brain was like reading Hegel. But I persevered, trading the stifling heat of Phoenix in July for the frosted spires of the White Witch’s palace, the breezy meadows of the Shire, and eventually the fire-lit stone hearths of Hogwarts. By middle school, I was about a dozen pages and twenty-something sketches into my own fantasy world, an unmistakably British ripoff that, for better or worse, never saw the light of day.

It wasn’t until high school, by which time my artistry had taken a turn toward songwriting, that I learned about the religious underpinnings of these writers and their fantastic creations. I traded The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Return of the King for books like Mere Christianity and The Screwtape Letters, the latter of which served as the cornerstone of my college application essay. So you can imagine how full-circle it felt when, as a philosophy undergrad at Princeton, I had the opportunity to spend six months as a visiting student at Oxford, the intellectual home of the very authors to whom I felt I owed so much.

Oxford in January was stoic and damp, and it didn’t help that Princeton’s archaic exam schedule had me locked up in the Bodlein before I’d even finished unpacking. I spent the first two weeks taking final exams for my American classes, courses like statistics and astrobiology, even as I juggled newly assigned essays for my British tutorials, fun stuff like history of eugenics and philosophy of mind. And yeah I know, I can’t complain—not only was it a ridiculous opportunity, but the rough start made it all feel that much more scholarly and dramatic, similar to what I’d imagined. Unlike the gothic architecture of the colonial-era American Ivies, Oxbridge architecture is actually medieval, and you can feel it. My last overlapping American exam was biochemistry, and as I walked across a misty Christ Church Meadow, passed by the Radcliffe Camera, ascended the steps to my home college of Hertford, crossed over the Bridge of Sighs, and ascended the slippery spiraling staircase smoothed over by centuries of neurotic posh poulaines, I was fully caught up in the great mythos, the fantastic heart of Oxford that surely buoyed the imaginations of Tolkien and Lewis. The rocks in the old walls seemed to cry out: everything you do in this place is sacred, no matter how seemingly small or mundane. Every conversation, every assigned reading, every frantic clap of your keyboard is part of a greater story, sub specie aeternitatis. A beautiful irony, what with so many of our philosophy cohort being moral nihilists.

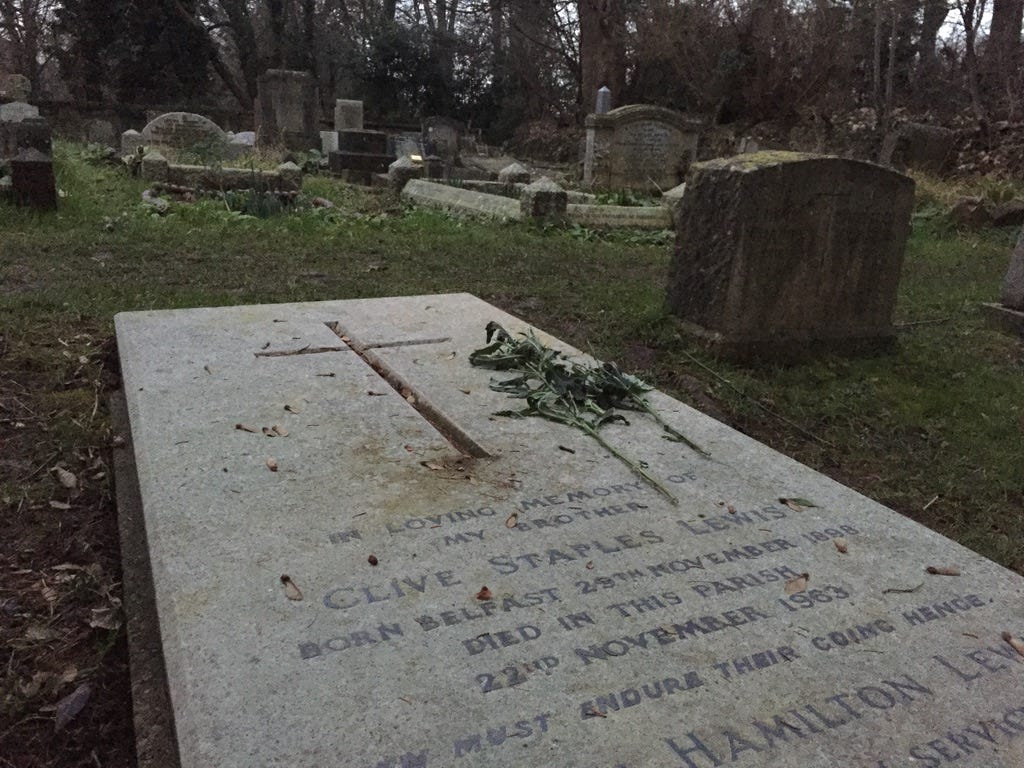

I emerged from that stuffy old room triumphant, unsure whether I’d passed biochem but at least certain of my immediate purpose. After a brief second breakfast in Hertford’s oh-so-Hogwarts dining hall, I set out on my pilgrimage. I first followed the curving High Street to Magdalen College, where C.S. Lewis had been a tutor and had his “reluctant” conversion experience, taking extra time to meander through Deer Park, where I envisioned Tolkien and Lewis riffing under smoke rings of tobacco. Then waaaay up Headington Road until it became London Road (giddy up), right again, left, and… the Kilns. The humble home of Lewis, which appeared vacant and whose backyard pond was honestly pretty gross. Finally, onto Holy Trinity Church, where I had for so long imagined myself loitering over Lewis’ grave like Harry and Hermione in Godric’s Hollow. It was one of the quietest, most sacred days I’d ever experienced, a sort of west-coast protestant pilgrimage. (I tried to rinse and repeat for Tolkien, but a lonely pint in The Eagle and Child pub followed by a rainy walk to yet another gothic graveyard didn’t deliver the same magic. Maybe I needed to be Catholic?)

As you can imagine, this protestant pilgrimage turned out to be the peak of my anglophilia, and the descent was less romantic. Between being the only American on our men’s rowing team (though they unironically loved Southern pop country music, yes, really) and being repeatedly chastened for American flubs (“Bathroom? Do you want to take a bath?”), my British adventure only made me acutely aware of how not at all British I actually am. I was finally sober enough to accept that maybe even my British heroes weren’t as knightly as I’d hoped.

If you’re still reading, I’m gonna assume that you, too, have been touched by the lives and loves of Inklings like Lewis and Tolkien. Brace yourself.

Did you know, for example, that C.S. Lewis may have had a sexual relationship with his best friend’s mom? Did you know his philosophical defense of 3.5 billion years of pre-human animal suffering was that, well, maybe they’re collateral for the sins of the angels? Did you know that he wasn’t a professor of philosophy or theology but of medieval studies, and that some folks believe he was so humiliated in a debate with the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe (another point for Catholics) that he turned his focus more toward fiction over apologetics? I’m oversimplifying it, but I hope this helps you see why he was seeming more and more like Edmund and less and less like Peter to me.

As these things do, my anglophilia kept unravelling. By the end of my philosophy of religion tutorial, it wasn’t Richard Dawkins’ God Delusion that left me feeling existentially insecure but his critique that American culture is rootless and “derivative”, like a lesser Britain. (I tried to get a 1-on-1 meeting with Dawkins but his secretary seemed put off by my all-too-American enthusiasm.) And looking at our naming conventions, it’s hard to disagree. I live in NYC, where so many of the subway stops are shared by the London tube. Our most famous park is full of statues of Europeans who never even set foot in the States—this weekend alone I walked past Hans Christian Anderson, Beethoven, and Alice in Wonderland, not one of whom ever had a hot dog or made it to a Yankees game.

And I’m afraid that the damage is done, with the anglophilia so deeply embedded in my early artistic formation that I couldn’t escape it if I tried. The first creative community that really took to my songwriting is called “The Rabbit Room”, named after the spot where Lewis, Tolkien, and the other Inklings convened to discuss their projects. I actually released my debut EP just before I arrived in the UK and cut my teeth busking it up and down High Street. And for the album art, I sent my friend Jack references that included a sketch of Puddleglum, the humble hero from The Silver Chair, the penultimate book in Lewis’ Narnia. Which is all to say, I’m hopeless.

Fittingly, though, it was none other than Puddleglum who helped me implode this latest, most cynical mirage concerning my childhood heroes. There’s a climactic scene toward the end of The Silver Chair where Puddleglum, trapped with his friends in the witch’s underground lair, is tempted to despair that Narnia never actually existed—to which he replies:

“Suppose we have only dreamed, or made up, all those things—trees and grass and sun and moon and stars and Aslan himself. Suppose we have. Then all I can say is that, in that case, the made-up things seem a good deal more important than the real ones. That’s why I’m going to stand by the play-world. I’m on Aslan’s side even if there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. I’m going to live as like a Narnian as I can even if there isn’t any Narnia.”

We could debate the orthodoxy of Puddleglum’s theological position. The Apostle Paul seemed to think the early Church was pretty pitiful if everyone was dying over a bunch of lies (1 Cor. 15:19). To my reading, Lewis doesn’t repeat this edgy (dare I say, American) pragmatism in his other non-fiction works. It seems like Narnia, his fantasy world, is where he feels safe enough to really challenge pervasive theological norms, to swing for the fences. And that’s where he and I made a new truce.

I’m not British, and though I will occasionally ask “where’s the loo” to remind you I studied abroad, I no longer pine for medieval gothic halls, re-runs of stories about knights and dragons, and a perfect American analog to British pub culture. C.S. Lewis and the Inklings don’t inspire me for their accents, pipes, gardening, intellect, philosophy, or wordsmithing; they inspire me because they created undeniably British worlds that were nonetheless sufficiently unlike Britain so as to transport the reader to that higher plane, allowing them to escape reality only to return renewed and re-inspired, better equipped to bring heaven down to earth. They’re still my heroes, not because they’re so posh and brilliant, but because they’re hard-working creatives who on some level understood their vocation as one unconstrained by the economic and industrial machines that keep us looking down. They looked up, and whether or not Narnia or Middle Earth were ever real, the Inklings helped some of us live into a reality more beautiful than the one we’d have experienced if we hadn’t looked at all.

So yeah, I still want to be an artist like that. I want to build worlds out of songs that allow folks to live into a higher reality. But now I want them to sound distinctly American, whatever that means, because that’s what I am. Loud and proud and all-too-enthusiastic.

Below you’ll find my next attempt at swinging for the fences. It’s a song I’m tremendously proud of, about that Phoenix July that I was always trying to escape. I hope it takes you there.

-J

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to J Lind's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.